“There’ll Be Another Time” |

by Teh Lag (2022)

|

From TSC:E 1.4's 2022 postmortem series.

(The following are solely the author's personal views and opinions.)

(The following are solely the author's personal views and opinions.)

Hey, everyone.

|

In 2003, barely out of elementary school, I got a copy of the newly-released PC port of Halo: Combat Evolved. In the following year, I discovered Halo Map Tools, SparkEdit, and PPF patch mods; thus setting in motion the events leading to me writing this retrospective as I approach the age of 30. Friends, family, and life milestones come and go; things that happened when you were a kid become quiet regrets in the back of your mind; cute little mods you shared with school pals gather virtual dust on N-th generation backup drives. I joined a certain modding team led by a certain person in early 2006, took charge in late 2011, and left after TSC:E shipped in 2015. These have all become distant memories.

|

In early 2021, riding an inevitable nostalgia for who we were and what we did in those long-past, sometimes-troubled glory days, a few of us reunited for one last tour. Another year has passed since then, and so here we are.

I wrote one of these retrospectives last time, too. This time, I don't have any grand statements about project management or questionable-if-well-intentioned pontification fetishizing "products" over "projects" (as if there were no higher aspiration for independent art than replicating signifiers of the cultural productions of capital. Look, we were young, it was the early 2010s, these things happen.)

Here are some final reflections on what the Evolved team did together.

I wrote one of these retrospectives last time, too. This time, I don't have any grand statements about project management or questionable-if-well-intentioned pontification fetishizing "products" over "projects" (as if there were no higher aspiration for independent art than replicating signifiers of the cultural productions of capital. Look, we were young, it was the early 2010s, these things happen.)

Here are some final reflections on what the Evolved team did together.

“They call it… Halo.”

Halo: Combat Evolved is a horror story in the tradition of popular sci-fi films from the decades preceding it. Alien, Aliens, The Thing: unsuspecting adventurers wander into - and quickly find themselves trapped in - a nightmare beyond their comprehension or capacity for resistance. An unknowable, inhuman enemy strips away any pretense of machismo or heroics, exposing the protagonists' own human frailty; they eke out a pyrrhic victory at best, as their understanding of their place in the universe is upended with no clear resolution. (That the humans in Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers live on in a wide-eyed, death-drive-infused denial of what they have become is a certain horror too, no?) Halo as a franchise went on to drift through the post-9/11 cultural landscape [1][2], toying with faux-political melodrama before settling into an odd mix of super-heroics, sacrifice-worshiping sentimentality, and lore fodder mixed with contemporary aesthetic pastiche. But, Halo - the first one - is old-school horror.

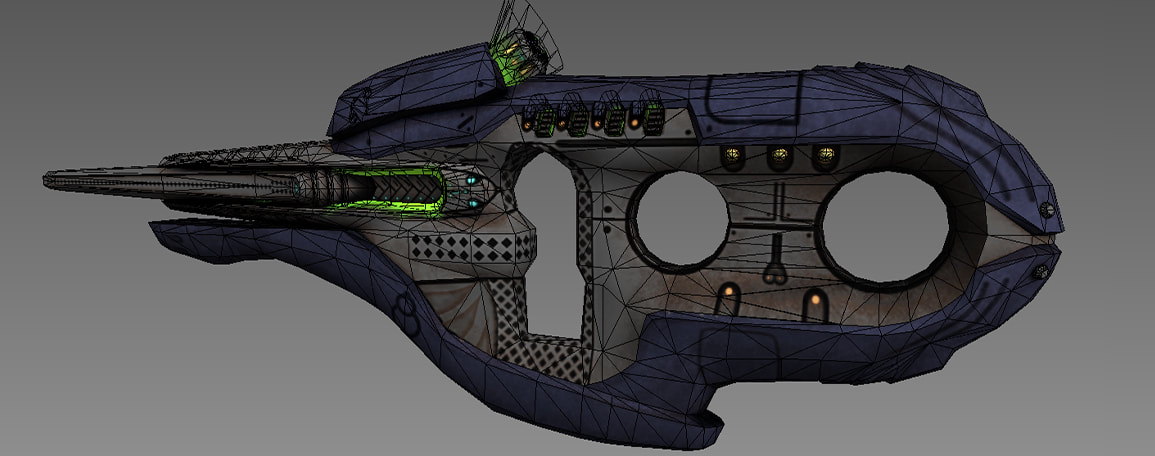

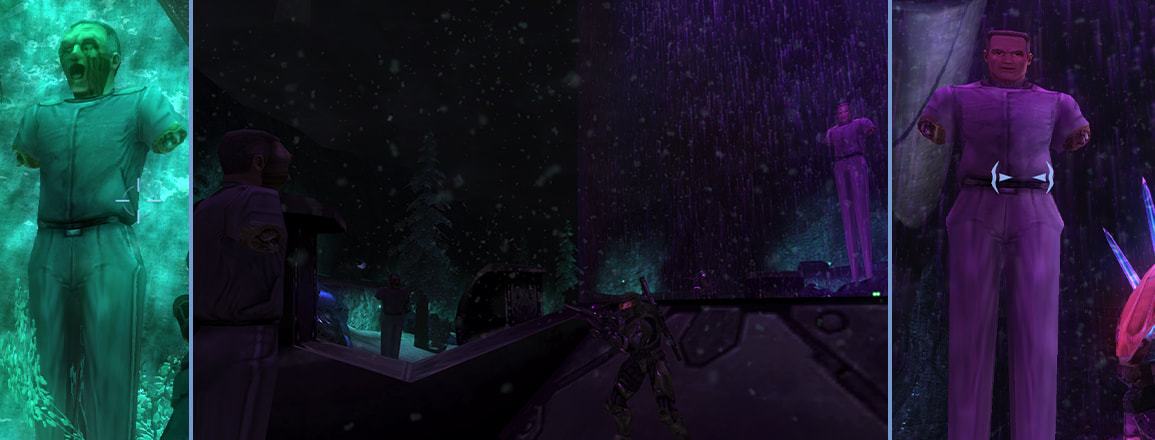

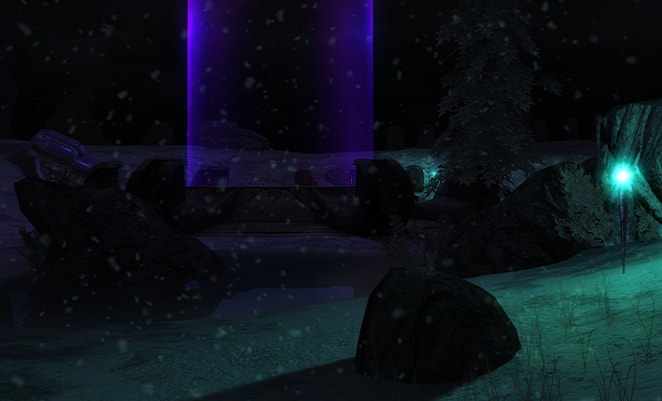

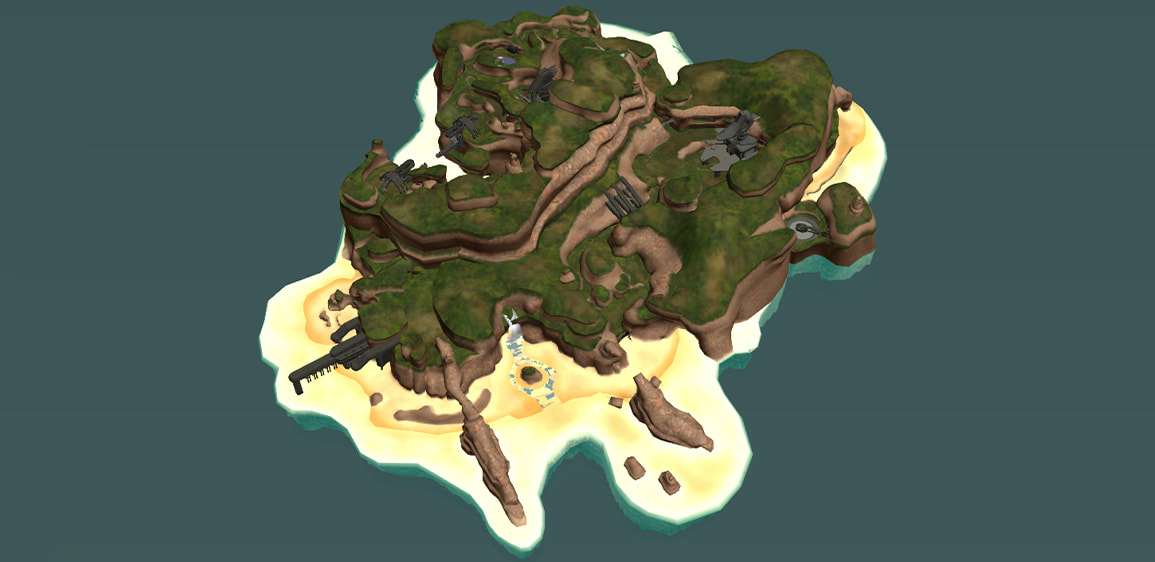

This reading informs TSC:E, which - filling in the broad strokes of the original level - chronicles the peak of the humans' time on Halo before they learn that they're not, in fact, going to save the day against impossible odds. The Master Chief and Cortana follow orders from their cocky, grizzled captain, staging a daring island raid to learn how to control a superweapon that will turn the tide of the war. They unlock doors they shouldn’t, descend into the cavernous bowels of a doomsday machine, and their captain disappears. As my teammates Silicon and Dafi once eloquently summarized: they think they're in an adventure movie, where the Cartographer shaft elevator would lead to a magnificent vista of bright, awe-inspiring underwater structures. Instead, the sunny optimism of the island exterior gives way to a distant approaching storm and the dark emptiness of the deep sea, threatening on all sides to crush a reception area that evokes the swamps surrounding the Flood labs. A reminder to visitors of the ring's terrible purpose, in a language our heroes cannot understand. This is the moment that their Star Wars underdog story dimension-shifts into a cosmic horror novella.

This reading informs TSC:E, which - filling in the broad strokes of the original level - chronicles the peak of the humans' time on Halo before they learn that they're not, in fact, going to save the day against impossible odds. The Master Chief and Cortana follow orders from their cocky, grizzled captain, staging a daring island raid to learn how to control a superweapon that will turn the tide of the war. They unlock doors they shouldn’t, descend into the cavernous bowels of a doomsday machine, and their captain disappears. As my teammates Silicon and Dafi once eloquently summarized: they think they're in an adventure movie, where the Cartographer shaft elevator would lead to a magnificent vista of bright, awe-inspiring underwater structures. Instead, the sunny optimism of the island exterior gives way to a distant approaching storm and the dark emptiness of the deep sea, threatening on all sides to crush a reception area that evokes the swamps surrounding the Flood labs. A reminder to visitors of the ring's terrible purpose, in a language our heroes cannot understand. This is the moment that their Star Wars underdog story dimension-shifts into a cosmic horror novella.

I always liked the theory that the island's security station unlocks the Flood facilities, which the Covenant then desperately try to re-seal and Keyes’ men self-assuredly pry back open. (Guilty Spark blames the aliens, but… well, he isn’t exactly known for being reliable - canon is what you make of it, nothing more.) There's something deliciously horrifying about making a terrible mistake with unfathomably far-reaching consequences without even realizing it, isn't there? Halo 4 similarly has Chief and Cortana unwittingly release Antagonist Man from his Sphere; I wonder if its writers came to similar conclusions.

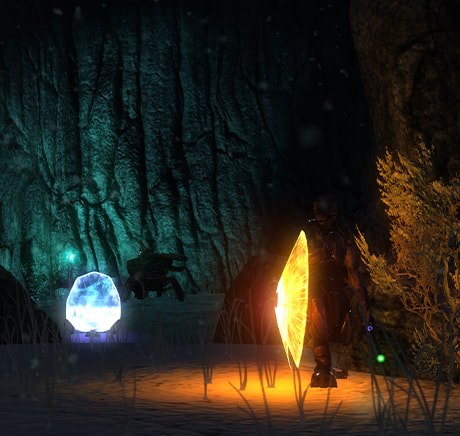

Details reinforcing these narrative conceits sprawl across the level: from the island map quietly shifting to a warning-light orange behind the Chief as he admires the view from security, to the island’s blue-and-orange beams, the orange ring segment on the Cartographer itself, and to the visual direction we pursued in the polish phase of the map's final segments - Silicon is particularly attached to the softly-howling vent tunnels emitting sickly green light. When early players bypassed security by launching Ghosts out a window, we added scripts (refined in 1.4) to support a parallel timeline where The Flood are never unleashed, Keyes never gets punched in the face, and - if we extrapolate from the CE-era backstory - the “gun pointed at the head of the universe” is placed into the hands of a humanity that kidnaps children to become enforcers for its fledgling space empire. Nobody learns anything, and a terrible cycle of galactic hubris continues. The day is saved!

Details reinforcing these narrative conceits sprawl across the level: from the island map quietly shifting to a warning-light orange behind the Chief as he admires the view from security, to the island’s blue-and-orange beams, the orange ring segment on the Cartographer itself, and to the visual direction we pursued in the polish phase of the map's final segments - Silicon is particularly attached to the softly-howling vent tunnels emitting sickly green light. When early players bypassed security by launching Ghosts out a window, we added scripts (refined in 1.4) to support a parallel timeline where The Flood are never unleashed, Keyes never gets punched in the face, and - if we extrapolate from the CE-era backstory - the “gun pointed at the head of the universe” is placed into the hands of a humanity that kidnaps children to become enforcers for its fledgling space empire. Nobody learns anything, and a terrible cycle of galactic hubris continues. The day is saved!

Speaking realistically, the visuals in our map's final segment were our best attempt at a coherent visual narrative given the extreme resource limitations we were under by the end of development. The tendril-like Demon Tree roots were my last-ditch effort to assemble something - anything - as a motif to fill unaccounted-for dead space without blowing our budgets. We quoted The Library’s claustrophobic catacombs because they filled a spatial niche and matched our narrative themes. If we had unlimited resources, maybe the underwater segment would have ended up looking like that adventure movie after all. A lot of effective creative direction, in my experience, is more about guiding good-enough compromises than perfectly executing grand up-front visions. (Wait, didn't I just say I wouldn't ramble about this sort of thing? Oh well.)

Blatant Revisionism

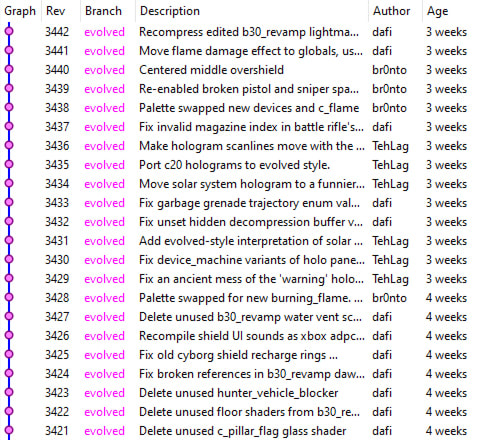

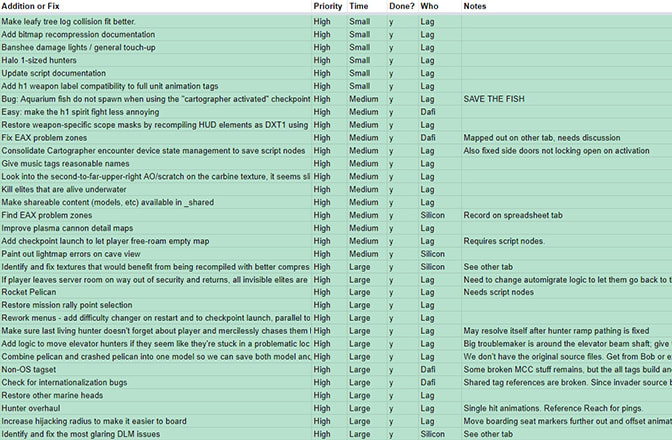

Anyway, 1.4. There were a handful of bugs that we wanted to fix. The Shotgun’s moving animation didn’t loop properly (a regression introduced in 1.3). Some easter eggs didn’t work when they should. There was one known reproducible crash. We probably could’ve fixed these when the mod first came out if we hadn’t been desperate to be done and move on with our lives.

But beyond that, making a “director’s cut” is dangerous: “where did we fall short at the time” easily becomes “what would we do now.” Our intent in 2015 necessarily includes the tradeoffs that we made to ship; early 1.4 ideas like cleaning up some underhanded AI spawn logic were deemed too invasive. By this metric, even bugfixes for 1.4 do involve revising history - but still, unintended rough edges are unintended. We decided on an ethos of “improvements” as things we couldn’t reasonably imagine wanting to revert. Clarifying the checkpoint alert text, tweaking unintuitive item placement: things that would seem “obviously correct”.

But beyond that, making a “director’s cut” is dangerous: “where did we fall short at the time” easily becomes “what would we do now.” Our intent in 2015 necessarily includes the tradeoffs that we made to ship; early 1.4 ideas like cleaning up some underhanded AI spawn logic were deemed too invasive. By this metric, even bugfixes for 1.4 do involve revising history - but still, unintended rough edges are unintended. We decided on an ethos of “improvements” as things we couldn’t reasonably imagine wanting to revert. Clarifying the checkpoint alert text, tweaking unintuitive item placement: things that would seem “obviously correct”.

…and then, we went and revised subjective design choices anyway.

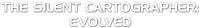

O, the Auto-Carbine. Circa 2014, we had wanted a new model to communicate that it was more versatile than the semi-auto gun players knew. Reality intervened, and instead we had to settle for adding the “Auto-” prefix to its name, hoping people would get the idea. It didn’t really work.

A replacement model was off the table for 1.4 - the Carbine is part of the level’s identity, as much as the ODSTs or the lighting's color temperature. How could we better-communicate its behavior in a way that would cleanly fit in? We settled on VFX, which we had already used extensively to communicate gameplay information. In particular, the Plasma Rifle’s vents glow and emit sparks at high rates of fire!

A replacement model was off the table for 1.4 - the Carbine is part of the level’s identity, as much as the ODSTs or the lighting's color temperature. How could we better-communicate its behavior in a way that would cleanly fit in? We settled on VFX, which we had already used extensively to communicate gameplay information. In particular, the Plasma Rifle’s vents glow and emit sparks at high rates of fire!

Extrapolating to a general motif, Dafi and I gave the Carbine a similar effect to encourage automatic use. A light show can be a cute reward for players engaging with a mechanic correctly, and I’m happy with the end result. Much of 1.4 came from extrapolating existing trends to guide subjective improvements.

Next up: the Hunters. My sweethearts.

The Hunter is my favorite unit in Halo. Massive, intimidating, overpowering, seemingly-invincible until you learn how to dance with her. Hunters suggest a character action-like take on combat that the series never quite manifested: learning weak spots, reading animation cues, attack combos that challenge player habits. We had grand designs for 1.4: retouched visuals, stagger damage like in Reach, a prototype implementation for directional melees like in the later games to punish players for dancing carelessly. (Much of this had to be cut, on a joint account of resource limitations and my own burnout midway through 1.4’s production – but more on that in a bit).

Some people think TSC:E’s Hunters are too dangerous, but I think they’re the right amount. In retrospect, their gameplay revisions probably would’ve gone too far. I tweaked some of the unit’s parameters to make them more visually responsive to damage, and gave them a fresh coat of paint within the conventions of SOI_7 and Dafi’s original texture work. Silicon has already explained the work we did to improve their showcase arena, so I’ll leave it at that.

At the far end of this spectrum of changes was the Brutes.

It needs to be said: the characterization of "Brutes" as violent, comparatively primitive aliens, with chieftains and headdresses and references to cannibalism, is loaded with coding. Halo 2 refers to its Brute antagonist as "Mister Mohawk". Indeed, prior critical analysis of the characters in Grace in the Machine's Alien Bastards: Genocide and the Other in Halo 2 describes them as "smack[ing] of colonial racism" [3] - it’s a bit much.

Whether or not Bungie intended to perpetuate such unfortunate associations, the sci-fi tropes from which Halo derives its own aesthetic conventions are entwined with real-world histories of colonialism and racialization. (What did I say earlier about cosmic horror novellas…?) In 2004, Bungie was riffing on movies like Predator (1987), loaded with their own cultural baggage - Aliens and Predator in particular draw on US intervention in Vietnam and Latin America. In 2022, I wouldn’t know where to begin untangling Halo as a whole, and I don’t envy people whose job is to do so.

It needs to be said: the characterization of "Brutes" as violent, comparatively primitive aliens, with chieftains and headdresses and references to cannibalism, is loaded with coding. Halo 2 refers to its Brute antagonist as "Mister Mohawk". Indeed, prior critical analysis of the characters in Grace in the Machine's Alien Bastards: Genocide and the Other in Halo 2 describes them as "smack[ing] of colonial racism" [3] - it’s a bit much.

Whether or not Bungie intended to perpetuate such unfortunate associations, the sci-fi tropes from which Halo derives its own aesthetic conventions are entwined with real-world histories of colonialism and racialization. (What did I say earlier about cosmic horror novellas…?) In 2004, Bungie was riffing on movies like Predator (1987), loaded with their own cultural baggage - Aliens and Predator in particular draw on US intervention in Vietnam and Latin America. In 2022, I wouldn’t know where to begin untangling Halo as a whole, and I don’t envy people whose job is to do so.

Cut to: TSC:E’s Brute encounters, marked by the giant metal pillars on which they hang weapons and bodies as trophies. Design-wise, we wanted to give the player item caches with more variety than already-ubiquitous squads of dead Marines. Halo 2 suggests that Brutes collect guns and skulls, and the rest seemed to write itself. As set dressing, the pillars bring a strain of disturbing violence, foreshadowing just what kind of movie our hapless heroes have wandered into. In direction, I could’ve done better. Taken together, the skewered bodies and simplistic cloth flags (I had specifically requested the flags) reinforced an uncritical, similarly-coded interpretation of the characters. It’s also an incongruous visual element against the future-industrial, machines-and-lights style of their armor and weapons, seeming to denote these cultural artifacts as inherently less sophisticated than the rest of the Covenant.

Thinking about how to make the concept and execution more complex and less bland within the bounds of what we shipped in 2015, Halo 2’s hologram flags came to mind. The goal was to complicate the Brutes’ visual and narrative characters: assimilated into the Covenant hegemony, conveying a distinct history while also, in this new interpretation, bound by symbols of their military service. Aliens with a certain subjectivity, who could project any image, but are projecting this - an attempt, at least, to consider how members of the Covenant shape and are shaped by their participation in it.

Thinking about how to make the concept and execution more complex and less bland within the bounds of what we shipped in 2015, Halo 2’s hologram flags came to mind. The goal was to complicate the Brutes’ visual and narrative characters: assimilated into the Covenant hegemony, conveying a distinct history while also, in this new interpretation, bound by symbols of their military service. Aliens with a certain subjectivity, who could project any image, but are projecting this - an attempt, at least, to consider how members of the Covenant shape and are shaped by their participation in it.

The updated flag was fun to create: it riffed on our prior colorful Forerunner hologram VFX and added a new circuit effect to reinforce the jarring synthesis of unfathomably advanced technology with the physicality of tattered cloth. After some prodding from Dafi (who was initially unconvinced), I further retouched the pillar’s textures to match the Brutes’ energized, fire-spewing guns; the end result was something all three of us felt was more coherent and interesting. I don’t think we challenged Halo’s fundamental problem of having big violent ape aliens called “Brutes” - their inclusion in the mod predates our more critical approach to the franchise - but I do think reconsidering their execution and characterization was worthwhile.

Then, Noble mode. Noble was always a project in metatextual dialogue with both the level and its production history; as such, we felt comfortable updating it beyond the original.

…But more on that in a bit.

Twilight of the Golden Gun

The island’s many easter-egg weapons - referred to as “gold guns” - have an unhappy origin.

This story begins in 2011, as the modding team then-known as CMT was developing a demo of its SPv3 mod for the map The Truth and Reconciliation; the team had collectively decided I should take leadership of the project midway through. After an exhausting and combative internal argument over whether the mod’s silenced SMG should have a scope, our non-scope faction ultimately won out. The scope was my fault: I had doodled the model some time towards the end of the ill-fated development of SPv2 circa 2009, and the prevailing attitude was still, in many cases, “as many assets as possible for as many features as possible”. Team dynamics were such that removing features required a devil’s proof that there was no fun to be gained by, i.e., sticking a scope on a short-range spray-and-pray weapon. (Rather than coming to an understanding that we wanted the mod’s sandbox philosophy to be more restrained and coherent - but, Dafi has written about that.)

Venting my frustration at how difficult the issue had been to resolve, while not wanting to waste the asset, I added a gold-plate shader, absurd weapon stats, music to play when it fired, and hid this “Super Machine Gun” in the map. Bungie had set precedents for similar easter eggs in Halo 2's Skulls and Scarab Gun, and this became a running solution, both for releasing development frustrations and for finding homes for assets that didn’t fit our nascent design ethos. We could incorporate content while explicitly acknowledging that it didn’t fit within the main text of the mod, via gold plating, gaudy effects, and so on.

This story begins in 2011, as the modding team then-known as CMT was developing a demo of its SPv3 mod for the map The Truth and Reconciliation; the team had collectively decided I should take leadership of the project midway through. After an exhausting and combative internal argument over whether the mod’s silenced SMG should have a scope, our non-scope faction ultimately won out. The scope was my fault: I had doodled the model some time towards the end of the ill-fated development of SPv2 circa 2009, and the prevailing attitude was still, in many cases, “as many assets as possible for as many features as possible”. Team dynamics were such that removing features required a devil’s proof that there was no fun to be gained by, i.e., sticking a scope on a short-range spray-and-pray weapon. (Rather than coming to an understanding that we wanted the mod’s sandbox philosophy to be more restrained and coherent - but, Dafi has written about that.)

Venting my frustration at how difficult the issue had been to resolve, while not wanting to waste the asset, I added a gold-plate shader, absurd weapon stats, music to play when it fired, and hid this “Super Machine Gun” in the map. Bungie had set precedents for similar easter eggs in Halo 2's Skulls and Scarab Gun, and this became a running solution, both for releasing development frustrations and for finding homes for assets that didn’t fit our nascent design ethos. We could incorporate content while explicitly acknowledging that it didn’t fit within the main text of the mod, via gold plating, gaudy effects, and so on.

We wanted to carry the tradition forward in TSC:E, and the team added more jokes riffing on absurdities we encountered. Towards the end of development, we had lots of momentum but were often partially idle as we waited on art assets, lightmap renders, or just needed to blow off steam - so, we ended up creating a full roster of gold guns. If you know you'll have the urge to keep making new stuff, it’s probably better to direct it at things that won’t get tangled up in a dependency web with the rest of production.

To get academic for a bit: Weinel et. al [4] broadly characterize a spectrum between two forms of hidden feature in software development:

1. The humorous, quirky easter egg, which though enjoyable, is unrelated to the main application.

2. The easter egg which corresponds thematically to the main programme, contributing to its artistic form as a whole.

2. The easter egg which corresponds thematically to the main programme, contributing to its artistic form as a whole.

The gold guns are a bit of each. They’re meant to entertain players who go looking for them and increase replay value - but, concurrently, they reinforce our take on Halo’s sandbox, relieving our core design from compromises that would need to be made to accommodate more content. They expand the domain of the mod’s text, allowing us as designers to continue engaging with players outside the diegetic space so coveted by “immersive” experiences. (Immersion as a strict design aesthetic of “realism” strikes me as odd; I want to immerse players in the experience of play, which includes the presence of the designer!) TSC:E is informed by a philosophy of games as a two-way interaction between designer and player; the player plays and is played with. We often joked that our combat encounter scripts were written like we're becoming the Arbiter playing a game of Halo Wars against the Chief, and I wanted to likewise embody us as designers across the mod’s development history.

That said, I repeat that these are not all happy stories. In describing the infamous Hall of Tortured Souls that shipped with Microsoft Excel in the 1990s, Weinel at. al [4] casually offer a grim assessment:

The inclusion of easter eggs such as the ‘hall of tortured souls’ seems to stem from the grueling process of software development. The easter egg may have given the programmers some cathartic satisfaction; an opportunity to work briefly on something whimsical and funny, providing release from the more serious aims of the project.

The opportunity to develop our ideas about play and immersion should not obscure that development was difficult and painful. The original golden gun was a product of frustration with an unhealthy team environment. Halo 2’s development cycle was legendarily brutal. The need to exorcize development pains also led to the Keyesman sequence in T&R 2012, which went on to inspire TSC:E’s metatextual horror-comedy experiment in Noble mode. These are not happy stories. (The map does have more eggs, most with some sort of story behind them, some happier than these.)

In TSC:E 1.4, we resurrected the SMG easter egg, which was absent from the original release. The regular SMG doesn’t appear in the map, unlike every other gold gun which had a 'real' equivalent. I regretted not having the resource capacity to ship the assets in 2015, but we had room with some clever reshuffling. It’s not the same as it was in 2012; neither are we. It reflects our return to increasingly-hazy memories rather than ongoing struggles and absurdities. Maybe it is a happier gun as a result? Or maybe it is even more bitter after 6 years?

Sleep peacefully, my beloved gun, the SMG.

“Regret, Regret, Regret”

The Past

TSC:E started as an experiment. To give an abridged history – after the February 2012 T&R release, we tossed around ideas for future work. CMT’s founder and former lead, Masterz (who I had replaced), advocated for continuing the SPv3 mod, and possibly finishing a custom campaign we’d inherited, then called Bridge CE. Eventually, a few of us instead coalesced around remaking a Halo: CE level from the ground up, and we chose TSC because it was a good fit for the assets we had. If it was successful, we’d consider making more. We brainstormed, sketched a vague layout, and concept artist and then-design contributor Axial produced a more comprehensive one. After a long period of back-and-forth, SlappyThePirate produced an environment sample for the beach landing area; Dafi and I figured out the encounter; I scripted it, and it was ingame by April. Slappy’s excellent arena layout, combined with a moody sunrise and some sort of magic conjured in the encounter design, convinced us we were onto something.

Internally, we made a plan. Our former lead would continue SPv3, Dafi would head this remake, and I would lead the team’s shared content development and infrastructure while providing direction (eventually leading me to become TSC:E’s overall director). Slappy, Silicon, Dafi and I worked on environments and scripting, and...

...things got complicated.

...things got complicated.

By the end of the year, issues were piling up. Slappy and Axial both parted ways with the team; Silicon, BobTheGreatII, and later LlamaJuice stepped in with heroic efforts to guide and execute environment design, and the original layouts fell by the wayside. Each school semester periodically left me burned out for weeks at a time. (Dafi, Silicon, and I often consider some of the more simplistic arena layouts the two of them designed, like the Brute Bowl and L-Room, to be a result of my absence - though, honestly, I think they’re fine, and they resulted in us considering our arena design goals more carefully in the future.) We worked with just-in-time planning, often lacked critical assets, and had to course-correct major elements when they encountered realities of the map’s evolving pacing and design philosophy. The overhaul of the Security Pit layout, discussed in my 2015 article, was one such example.

It's, maybe, an open secret that tensions were high between TSC:E’s core team and SPv3's lead. Attempts to manage internal divisions included the “don’t give other people work to do” mentality I harped on in 2015 (with, alas, little self-awareness about how it might affect my interpersonal relationships as a whole); and a “whoever works on a task gets to make the final call” design process, to reduce cross-project entanglements and reign in “ideas guys” casually dictating work to teammates (brushing against, but not quite grasping, the idea that it’s fundamentally exploitative to treat people in an art collab as disposable labor.)

We reduced power concentration in leads by making the dev process more transparent to contributors, culminating in a team-wide version control system to make the content base reviewable, editable, and buildable by everyone. We reorganized our rapidly-diverging gameplay assets as it became clear that Evolved and SPv3’s differences couldn’t be reconciled. Our content base carries deep scars from these conflicts - but, so do we. Incremental changes couldn’t patch over deep-rooted dependence on the team’s structure or our own immaturity.

As the overall lead, it was my responsibility to ensure everyone got the healthy environment they deserved - not the least important when spending time on a for-free fan project. After the ugliest days of T&R, I wanted the team to nurture its members, to bring out the best in each other and for everyone to put in efforts that uplifted everyone else’s. Instead, the toxic atmosphere persisted and often brought out the worst in us: long evenings were spent trying to manage what little trust remained between project leads; long messages were exchanged in online broadsides, as one camp criticized the other's design or pointed out long-unfixed bugs buried under myriad features. My failure to control the situation grated on my Evolved teammates, and Dafi and Silicon repeatedly had to talk me out of a) wanting to pull TSC:E out of CMT or b) quitting the project myself as it wore me down. Ultimately, we didn’t want to find out what a CMT breakup would look like so deep into production. We wanted to finish the mod for the sake of everyone who had worked on it - or, in other words, our emotional investment in the project had trapped us.

We reduced power concentration in leads by making the dev process more transparent to contributors, culminating in a team-wide version control system to make the content base reviewable, editable, and buildable by everyone. We reorganized our rapidly-diverging gameplay assets as it became clear that Evolved and SPv3’s differences couldn’t be reconciled. Our content base carries deep scars from these conflicts - but, so do we. Incremental changes couldn’t patch over deep-rooted dependence on the team’s structure or our own immaturity.

As the overall lead, it was my responsibility to ensure everyone got the healthy environment they deserved - not the least important when spending time on a for-free fan project. After the ugliest days of T&R, I wanted the team to nurture its members, to bring out the best in each other and for everyone to put in efforts that uplifted everyone else’s. Instead, the toxic atmosphere persisted and often brought out the worst in us: long evenings were spent trying to manage what little trust remained between project leads; long messages were exchanged in online broadsides, as one camp criticized the other's design or pointed out long-unfixed bugs buried under myriad features. My failure to control the situation grated on my Evolved teammates, and Dafi and Silicon repeatedly had to talk me out of a) wanting to pull TSC:E out of CMT or b) quitting the project myself as it wore me down. Ultimately, we didn’t want to find out what a CMT breakup would look like so deep into production. We wanted to finish the mod for the sake of everyone who had worked on it - or, in other words, our emotional investment in the project had trapped us.

I still feel that, in dedicating myself to TSC:E, I ended up abandoning the other side of the team to the same leadership and direction issues that we ourselves were trying to insulate against. Creative relationships can become every bit as painful, even abusive, as any other; and collaborators who neglect, or are allowed to neglect, their responsibilities to care for and respect teammates often leave a trail of hurt people behind them. I still don’t know if we, or I, made the right decisions. Everyone deserved better than I was able to provide. Draw what conclusions you will regarding SPv3.

By 2013, it was clear that this wasn’t an experiment – it was a swan song. We went all-out, and roles blurred: I did a large chunk of environment polish work and layout revision, Dafi and Silicon collaborated on texture art, and just about everyone on the team helped with what they could. Being fair to ourselves: our coping strategies did help us keep scope under control, help our project develop its own identity, and allow us to ship the map. In 2015 we finished, and then many of us left it all behind.

By 2013, it was clear that this wasn’t an experiment – it was a swan song. We went all-out, and roles blurred: I did a large chunk of environment polish work and layout revision, Dafi and Silicon collaborated on texture art, and just about everyone on the team helped with what they could. Being fair to ourselves: our coping strategies did help us keep scope under control, help our project develop its own identity, and allow us to ship the map. In 2015 we finished, and then many of us left it all behind.

The Present

When Silicon, Dafi, and I reunited in 2021, things were different. We’d discussed it a lot over the intervening years, but it was almost overwhelming to realize we weren’t mired in those toxic dynamics anymore. I didn’t have to put up a facade of “Lag, the confident and in-control leader", fight for the project’s autonomy, or worry about a parallel development effort. Silicon and Dafi freely took on leadership roles like task tracking and handling our community presence. This was healthier for all of us.

There were still challenges. In the old days of our youth, we regularly pulled 40-to-80 hour weeks modding - even less advisable now than it had been then. After a few months staying up later than I should have on 1.4, I hit a wall: exertion catches up with you, years of stress have a way of staying with you, and there were memories that I wasn’t ready to face. Old arguments and awful nights from years prior regularly came flooding back. It took serious emotional work to overcome, and I once again found myself unable to contribute for weeks at a time – as Silicon dutifully held down the fort working on lighting touch-ups. If there’s one thing I want to communicate here, it’s that things didn’t have to happen like this - not back then and not in 2021 - and TSC:E could’ve been even more if they hadn’t. Burnout and trauma are real, and the past has consequences for the present, even when you're just doing something for fun.

We tried to end on a pleasant note. For TSC:E's public source file release, we’d spun off a content set that mirrored classic Halo: CE gameplay in our visual style, and to showcase it in 1.4 we returned to The Truth & Reconciliation. We ported the old publicly-released 2012 environment assets - some discarded by the SPv3 project long ago - back to the original scenario; a chance to finally create a world free from ghosts that had continued to haunt us. The three of us collaborated on re-doing BSP portals, re-rendering lightmaps, and making everything look as good as we could manage before its final send-off. Maybe it was something like preparing a corpse for a memorial service?

We tried to end on a pleasant note. For TSC:E's public source file release, we’d spun off a content set that mirrored classic Halo: CE gameplay in our visual style, and to showcase it in 1.4 we returned to The Truth & Reconciliation. We ported the old publicly-released 2012 environment assets - some discarded by the SPv3 project long ago - back to the original scenario; a chance to finally create a world free from ghosts that had continued to haunt us. The three of us collaborated on re-doing BSP portals, re-rendering lightmaps, and making everything look as good as we could manage before its final send-off. Maybe it was something like preparing a corpse for a memorial service?

One of the last assets we checked in for 1.4 was a recording of Silicon, Dafi and myself singing Jingle Bells in Grunt voices for an easter egg. It was supposed to be a fun capstone to the development effort. Instead, we then tripped up on last-minute build complications that took another two days to fix, as we became increasingly tired, stressed, and frustrated with this 2001 game engine…

…Well, some things never change.

…Well, some things never change.

The Future

Off in a parallel universe, Quake (1996) had undergone what Robert Yang, writing for Rock Paper Shotgun, described as a modding “renaissance” [5]. The quarter-century-old game is still a site of boundless creative expression, which Yang attributes to the longevity of the community that kept knowledge and history alive, and to tooling and engine upgrades (many enabled by ID's choice to GPL open-source it in 1999) that allow the community to keep creating and reinterpreting what Quake is. Back in our universe, the release of MCC’s official modding tools revived Halo’s early history of providing the community with serious content tooling, for the first time since Halo 2: Vista; and Halo likewise had a small but dedicated community keeping old knowledge alive, passed down from forum to forum across generations of modders. Moreover, much of the community we’d grown up in had matured and mellowed out. It was nice.

Halo, like most franchises of its scale, is now embedded in extractive microtransaction and games-as-a-service business models. But Halo can mean what we want it to mean. There’s something to be said for crafting our own visions and reinterpretations of this cultural artifact in a quiet, out-of-the-way nook of the modding community. This isn’t about venerating Halo the corporate IP, and it never was. It was messed-up kids lucky enough to have extensive PC access trying to find meaning in our lives; it was struggling against our personal demons and each other; it was forging interpersonal bonds and growing into our own as artists. It was a specific community that produced specific people, who got together to say, in some way, “we were here, and this is who we were.” Modding, for us, was much as Yang [5] summarizes:

Halo, like most franchises of its scale, is now embedded in extractive microtransaction and games-as-a-service business models. But Halo can mean what we want it to mean. There’s something to be said for crafting our own visions and reinterpretations of this cultural artifact in a quiet, out-of-the-way nook of the modding community. This isn’t about venerating Halo the corporate IP, and it never was. It was messed-up kids lucky enough to have extensive PC access trying to find meaning in our lives; it was struggling against our personal demons and each other; it was forging interpersonal bonds and growing into our own as artists. It was a specific community that produced specific people, who got together to say, in some way, “we were here, and this is who we were.” Modding, for us, was much as Yang [5] summarizes:

Quake modding symbolizes the opposite of work - it is life. And ultimately this is what the Quake Renaissance is about: when our communities control our own games - from the source code and tools, to the social hubs and archives - we can reinvent it as necessary, and through it, reinvent ourselves too.

Halo: CE, of course, is not open-source to the degree Quake is - so, how much is its future really in our hands? The labor expended on a project like TSC:E, when we repeat the artistic affects of capital with lavish 3d assets - who does it ultimately benefit and belong to? For an active Microsoft mega-franchise, power dynamics are such that we (effectively) serve at their pleasure. I’m increasingly disillusioned about perpetuating the aesthetic styles that uphold the game industry’s tech-as-progress narratives, or laboring on art that is often reincorporated into existing frameworks of private IP management (ranging from Steam Workshop to long-criticized labor practices at Roblox [6]). Still, our mods reflect the things we valued, the choices we made, and the risks we took to express ourselves using symbols from our culture - for whatever they’re worth.

Examining question like these means examining the nature of transformative fanworks. Fandom-studies scholars Hellekson and Busse (2014) [7] introduce their discussion of fanfiction by comparing “affirmative” and “transformative” fan engagement. “Affirmative” engagement considers a text as it exists; “transformative” engagement like fanfiction claims a text, in some part, for ourselves - reifying our interpretations, even “(sometimes purposefully critical) rewriting of shared media”. To me, making mods was akin to writing fanfic.

I see Keyes as a victim of his own arrogance; Cortana, unconcerned with the consequences of her actions until it is too late, reflecting the woman who created the unthinkingly competent Chief. Guilty Spark, an imperial functionary who cheerfully oversees mass death. The Forerunners, at once monstrous and pathetic, willing to destroy everything rather than accept the end of their galactic order; the Covenant, a dark shadow of what they were, and a portent of what the UNSC was becoming. It should give us pause to think about what, really, all the gray guns and tactical gear rhetorically represent in American games, produced amid America's 21st century wars, in stories echoing the cultural legacy of our wars through the 20th. (As elegantly stated by Molly Bloch in Bullet Points Monthly's Halo retrospective [8]: "Halo’s guns are a distraction, in the way that a toy distracts, but also in the way that propaganda distracts.") Examining contradictions that we had spent so long immersed in: that was what I wanted textually. “Players play and are played with”: that was what I wanted philosophically. Colorful, communicative art: that was what I wanted visually.

Examining question like these means examining the nature of transformative fanworks. Fandom-studies scholars Hellekson and Busse (2014) [7] introduce their discussion of fanfiction by comparing “affirmative” and “transformative” fan engagement. “Affirmative” engagement considers a text as it exists; “transformative” engagement like fanfiction claims a text, in some part, for ourselves - reifying our interpretations, even “(sometimes purposefully critical) rewriting of shared media”. To me, making mods was akin to writing fanfic.

I see Keyes as a victim of his own arrogance; Cortana, unconcerned with the consequences of her actions until it is too late, reflecting the woman who created the unthinkingly competent Chief. Guilty Spark, an imperial functionary who cheerfully oversees mass death. The Forerunners, at once monstrous and pathetic, willing to destroy everything rather than accept the end of their galactic order; the Covenant, a dark shadow of what they were, and a portent of what the UNSC was becoming. It should give us pause to think about what, really, all the gray guns and tactical gear rhetorically represent in American games, produced amid America's 21st century wars, in stories echoing the cultural legacy of our wars through the 20th. (As elegantly stated by Molly Bloch in Bullet Points Monthly's Halo retrospective [8]: "Halo’s guns are a distraction, in the way that a toy distracts, but also in the way that propaganda distracts.") Examining contradictions that we had spent so long immersed in: that was what I wanted textually. “Players play and are played with”: that was what I wanted philosophically. Colorful, communicative art: that was what I wanted visually.

In 2015, I wrote about "products" - making them, managing them - entirely begging the question of what we had produced. What is it, what does it say? At the end of production, what horrors have you birthed into the world? If you’re wondering why I bothered to write all this now, I guess I’d say something along the lines of Liz Ryerson’s 2019 piece on criticism, context, and cultural preservation [9]:

...you have to find some way to contextualize what you're doing, where you're coming from, and why you're doing it. otherwise you're free, like the rest of us, to vanish without a trace.

“To Sleep, Perchance to Dream”

Every location on the island holds memories. Populating the Brute Pool before the start of junior year. Sketching the Security Pit layout in a sleep-deprived haze after class; doing the same with the Hunter Arena, and then watching them descend the elevator for the first time. Scripting the Map Room during all-nighters in the leadup to graduation. The creeping realization that, for all the confidence I had in directing the project, I hadn’t known what I wanted to do with my life when it was done.

Halo, and its latest installment in Infinite, now has an uncertain relationship with the concept of endings - summarized in Bullet Points Monthly as “a series endlessly pushing itself forward and then back, a perfect ouroboros” [10]. We, however, can move on. In the years since our original release I've come out as a trans woman; I've tried other creative projects of varying success; I've learned new categories of ways to fuck up & try to make things right; I’ve made friends & lost friends & the world generally looks different than it did in March of 2015.

Despite regrets, I don’t regret the time we spent here. It's hard not to be proud: not just of the massive effort, but of how much everyone learned and grew. Evolving our processes beyond just passing ZIP files to some guy in charge was good for all of us. Learning what can happen when you don't know how to set boundaries on teammates' (or your own) behavior was painful but valuable. Getting to watch so many contributors blossom as creatives was something I'll cherish for the rest of my life.

I’m grateful. Not everyone gets to have an experience like leading the development of a multi-year fan project that gets tens of thousands of lifetime downloads, or the degree of community acclaim we somehow seem to have received. I'm sure I'll keep looking back and learning from everything that happened here for years to come.

Halo, and its latest installment in Infinite, now has an uncertain relationship with the concept of endings - summarized in Bullet Points Monthly as “a series endlessly pushing itself forward and then back, a perfect ouroboros” [10]. We, however, can move on. In the years since our original release I've come out as a trans woman; I've tried other creative projects of varying success; I've learned new categories of ways to fuck up & try to make things right; I’ve made friends & lost friends & the world generally looks different than it did in March of 2015.

Despite regrets, I don’t regret the time we spent here. It's hard not to be proud: not just of the massive effort, but of how much everyone learned and grew. Evolving our processes beyond just passing ZIP files to some guy in charge was good for all of us. Learning what can happen when you don't know how to set boundaries on teammates' (or your own) behavior was painful but valuable. Getting to watch so many contributors blossom as creatives was something I'll cherish for the rest of my life.

I’m grateful. Not everyone gets to have an experience like leading the development of a multi-year fan project that gets tens of thousands of lifetime downloads, or the degree of community acclaim we somehow seem to have received. I'm sure I'll keep looking back and learning from everything that happened here for years to come.

To my teammates then & now, & to the fellow Halo fans who've told us over the years that the island meant something to you: thank you.

~ The Lag

~ The Lag

References

[1] Sykes, David (2010), 9/11, the War on Terror, and ‘Halo’

E-International Relations

[2] Voorhees, Gerald (2014), Play and Possibility in the Rhetoric of the War on Terror: The Structure of Agency in Halo 2

Game Studies 14:1

[3] Benfell, Grace (2018), Alien Bastards: Genocide and the Other in Halo 2

Grace in the Machine

[4] Weinel, Jonathan et. al (2014), Easter eggs: Hidden tracks and messages in musical mediums

International Computer Music Conference Proceedings 2014

[5] Yang, Robert (2021), Quake Renaissance: a short history of 25 years of Quake modding

Rock Paper Shotgun

[6] Parkin, Simon (2022), The trouble with Roblox, the video game empire built on child labour

The Observer

[7] Hellekson, Karen and Busse, Kristina (2014), The Fan Fiction Studies Reader (Introduction)

University of Iowa Press

[8] Bloch, Molly (2022), Awake on Foreign Shores

Bullet Points Monthly January 2022 - Halo Infinite

[9] Ryerson, Liz (2019), make stuff and be free! (to vanish without a trace)

Patreon

[10] Teppelin, Rosarie (2022), Dust and Echoes

Bullet Points Monthly January 2022 - Halo Infinite

E-International Relations

[2] Voorhees, Gerald (2014), Play and Possibility in the Rhetoric of the War on Terror: The Structure of Agency in Halo 2

Game Studies 14:1

[3] Benfell, Grace (2018), Alien Bastards: Genocide and the Other in Halo 2

Grace in the Machine

[4] Weinel, Jonathan et. al (2014), Easter eggs: Hidden tracks and messages in musical mediums

International Computer Music Conference Proceedings 2014

[5] Yang, Robert (2021), Quake Renaissance: a short history of 25 years of Quake modding

Rock Paper Shotgun

[6] Parkin, Simon (2022), The trouble with Roblox, the video game empire built on child labour

The Observer

[7] Hellekson, Karen and Busse, Kristina (2014), The Fan Fiction Studies Reader (Introduction)

University of Iowa Press

[8] Bloch, Molly (2022), Awake on Foreign Shores

Bullet Points Monthly January 2022 - Halo Infinite

[9] Ryerson, Liz (2019), make stuff and be free! (to vanish without a trace)

Patreon

[10] Teppelin, Rosarie (2022), Dust and Echoes

Bullet Points Monthly January 2022 - Halo Infinite